Johann Hari, author of Chasing The Scream: The First And Last Days of the War on Drugs, wrote a short piece for the Huffington Post that outlines the premise of his book: the real reasons behind drug addiction.

We are all told as children that drugs are bad . When you take them, you will be hooked for life. So it’s better to get young kids to realize that drugs are bad. Very bad.

As time progressed, we were told that the chemicals in drugs caused users to become addicted. If a family or friend buckled to a drug’s siren call, then we should block them from our lives. This would help them fight the addiction.

But Johann Hari has questioned these approaches to addiction completely. He started off traveling over 30,000 miles in three and a half years to a broad range of people from very different backgrounds. All of them had personal experiences with addiction, and he began to make connections, learning from their stories. Hari Summarized what he learned. (1)

What is the Believed Cause of Drug Addiction?

Hari says, “If you had asked me what causes drug addiction at the start, I would have looked at you as if you were an idiot and said: “Drugs. Duh.” It’s not difficult to grasp. I thought I had seen it in my life. We can all explain it.”

He is talking about chemical hooks in drugs that cause our bodies to crave them. Many people still believe that the chemical makeup – and only the chemical makeup – of drugs causes addiction. (2)

Animal models have been showing us this fact for decades:

Drugs as the Root of Addiction Debunked

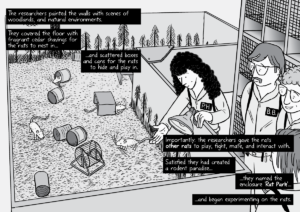

However, in the 1970s Bruce Alexander, then Professor of Psychology in Vancouver, noticed something about the experiments. All the rats were kept in empty cages and completely isolated. He decided to try the experiment again, but this time with much bigger cages, multiple rats, including a complete rat sanctuary. He called it Rat Park. (2)

And this is what happened:

“The rats with good lives didn’t like the drugged water. They mostly shunned it, consuming less than a quarter of the drugs the isolated rats used. None of them died. While all the rats who were alone and unhappy became heavy users, none of the rats who had a happy environment did.”

You can learn more about the Rat Park experiment here in cartoon form!

Human Equivalents

Yes, they are rats, and we are humans. It is different for us because our brains are more highly advanced. But, at the time, there was an unintentional equivalent to the Rat Park experiment happening with American soldiers in Vietnam.

“Time magazine reported using heroin was “as common as chewing gum” among U.S. soldiers. According to a study published in the Archives of General Psychiatry, 20 percent of U.S. soldiers had become addicted to heroin. When the war ended, many people were understandably terrified; they believed a vast number of addicts were about to head home. In fact, 95 percent of the addicted soldiers, according to the same study, just stopped. Very few had rehab. They shifted from an uncomfortable cage back to a pleasant one and began to reject the drug intake.”

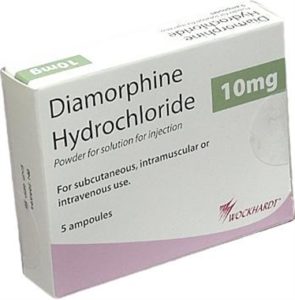

Hari picked up another example of human drug use that does not cause long-term addiction. If you are seriously injured, chances are you will be given diamorphine at the hospital.

Diamorphine is medical grade heroin and if the chemical hook was all it took to become addicted, people coming off months of diamorphine would be addicted, but that rarely ever happens.

“As the Canadian doctor Gabor Mate was the first to explained, medical users just stop, despite months of use. The same drug, used for the same length of time, turns street-users into desperate addicts and leaves medical patients unaffected.”

The chemical hook to addiction theory we were all taught is slowly starting to fade away, and Bruce Alexander’s approach is beginning to make more sense.

“The street-addict is like the rats in the first cage, isolated, alone, with only one source of solace to confide in. The medical patient is like the rats in the second cage. They are going home to a life surrounded by people full of love. The drug is the same, but the environment is different.”

Connection is the Cure to All that Ails Us

This whole quest for knowledge Hari took teaches us much more than how to help addicts. It shows us that we need to strengthen our current lifestyles and relationships.

“Professor Peter Cohen argues that human beings have a deep need to bond and form connections. It’s how we get our satisfaction. If we can’t connect with each other, we will connect with anything we can find. He says we should stop talking about ‘addiction’ altogether, and instead call it ‘bonding.’ A heroin addict has bonded with heroin because they couldn’t successfully bond as fully with anything else.”

Ask yourself: what have you bonded with? Are these simply more socially acceptable forms of drug, alcohol, or gambling addictions? Will this assist me in becoming the best version of myself?

“It is relevant to all of us because it forces us to think differently about ourselves. Human beings are bonding intelligence. We need to connect and love. The wisest sentence of the twentieth century was E.M. Forster’s — ‘only connect.’ But we have created an environment and a culture that cut us off from connecting on a deeper level. Start focusing on the cognitive interactions between you and your surroundings. And create yourself an omnipresent, omnipotent, superhero life.”

This leads us to a very startling and challenging concept:

“So the opposite of addiction is not sobriety. It is the human connection.” We have to love addicts, not ostracize them. This goes against everything we are taught and is very difficult to do.

But nothing is impossible when you have a magic mind, especially in Gloucester, MA.

Dr. Lloyd Sederer gives us another option:

“Mother Theresa, not someone often quoted in medical journals, said, ‘If you want to change the world, go home and love your family.'”

Hari knows this because addiction has always been an issue in his family. “It is hard to turn to your addicted family member and love them for who they are. But it is what we as humans need, love and acceptance.”

“When I returned from my long journey, I looked at my ex-boyfriend, in withdrawal, trembling on my spare bed, and I thought about him differently. For a century now, we have been singing war songs about addicts. It occurred to me as I wiped his brow, we should have been singing love songs to them all along.”

Take a look at Johann Hari’s TedTalk below. It is very enlightening!